The gut microbiome refers to the community of microbes living in the digestive tract, especially the large intestine. Each person has a unique microbial fingerprint shaped by genetics, diet, age, environment, and medication use (especially antibiotics). While some bacteria can cause disease, most are either harmless or beneficial.

Why Is the Gut Microbiome Important?

Digestion and Nutrient Absorption:

Gut microbes help break down complex carbohydrates, fiber, and proteins that our own enzymes can’t fully process. This enhances nutrient absorption and supports energy production.

Immune System Support:

Around 70% of the body’s immune cells are located in the gut. A balanced microbiome trains the immune system to distinguish between harmful and harmless invaders, reducing the risk of allergies and autoimmune diseases.

Production of Key Compounds:

Some gut bacteria produce vitamins (like B12 and K), and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, which help maintain the health of the gut lining and reduce inflammation.

Communication with the Brain:

The gut and brain are connected through the gut-brain axis. Microbes can influence mood and behavior by producing neurotransmitters like serotonin and sending signals to the brain through the vagus nerve.

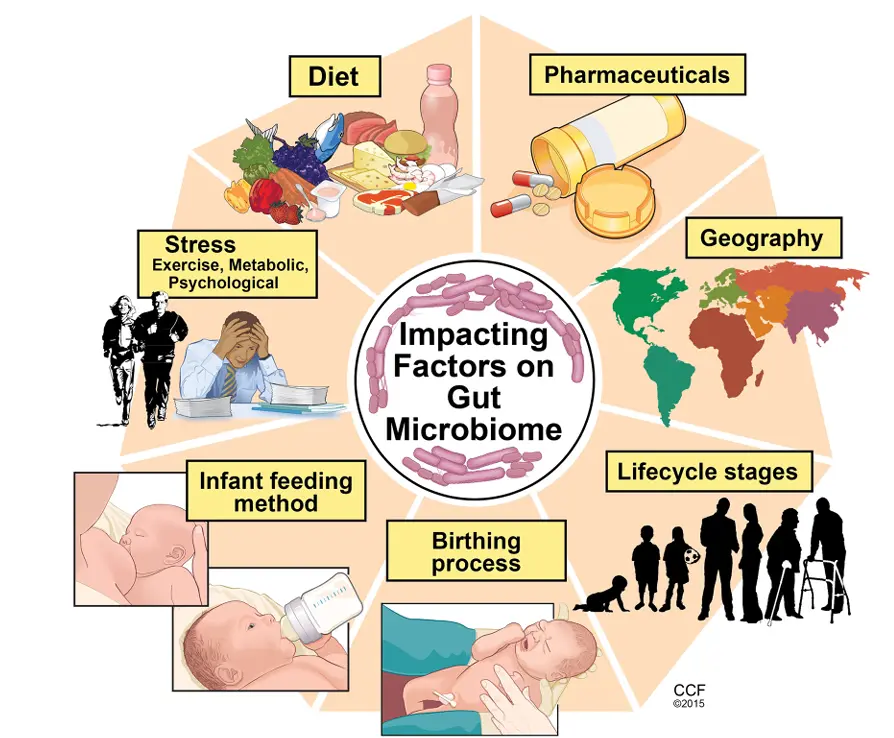

Factors That Affect the Microbiome

Diet: High-fiber, plant-rich diets support diverse and beneficial microbes. Diets high in processed foods and sugar can reduce microbial diversity.

Antibiotics: While essential in treating infections, antibiotics can disrupt gut bacteria and reduce microbial balance.

Stress and Sleep: Chronic stress and poor sleep can alter gut microbial composition, leading to imbalances known as dysbiosis.

Changes in the Gut Microbiome with Age

The Microbiome at Birth and Infancy

The gut is nearly sterile at birth, but colonization begins immediately through exposure to the mother and environment. The mode of delivery plays a major role—babies born vaginally acquire beneficial microbes like Lactobacillus, while C-section deliveries may result in delayed or altered microbial colonization.

In early infancy, feeding method matters:

- Breastfed infants tend to have a gut rich in Bifidobacteria, which support immune development.

- Formula-fed infants often develop a more diverse but less stable microbiome.

By age 2 to 3, the microbiome begins to resemble that of an adult, though it's still maturing.

Childhood and Adolescence

During childhood, the microbiome stabilizes and becomes more diverse. Exposure to new foods, environments, and social interactions helps build resilience and complexity in microbial communities. This period lays the foundation for long-term gut health.

In adolescence, hormonal changes can subtly influence microbial composition. Diet becomes a more dominant factor, as teenagers often adopt eating habits that can either support or disrupt microbial balance.

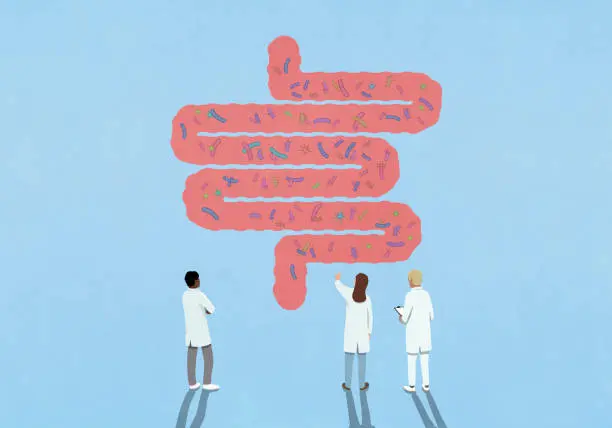

Adulthood

The adult gut microbiome is relatively stable but still responsive to lifestyle factors such as:

- Diet (especially fiber and fermented foods)

- Exercise

- Stress

- Medication use, especially antibiotics and NSAIDs

Healthy adults tend to have a balanced microbiome dominated by beneficial bacteria such as Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes, which aid in digestion, immune regulation, and nutrient production.